The Imaginative Beauty of New York's High Line

by Faith and John Stern

When the first half-mile of the High Line opened as an elevated public park in June 2009, it was an immediate success. Pleased visitors from all over the world, including crowds of New Yorkers, have flocked to it, ranging from many thousand on weekdays up to 100,000 on weekends. 1 What is it about this “park in the sky” that has attracted such interest?

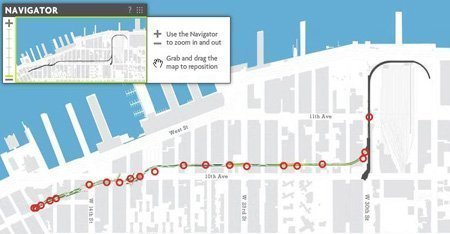

The answer, we believe, is in this principle of Aesthetic Realism, the education founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Many opposites are brought together in surprising ways in this public park being built along the old elevated railroad tracks running just west of 10th Avenue from 34th Street down to Gansevoort Street. They are opposites people want closer in themselves, such as Hard and Soft, Freedom and Plan, and above all, Self and World. It’s still a work in progress, but we believe the High Line will endure because it meets what Aesthetic Realism describes as the deepest hope in every human being: the hope to like the world on an honest and accurate basis.

Some History

The High Line was one section of a new route built by the New York Central Railroad in the early 1930s for its freight trains serving the West Side of Manhattan. It replaced the dangerous street trackage running from 60th Street along 11th and 10th avenues and West Street to a terminal just below Canal Street. (The train shown in the background is turning uptown from Canal onto West Street.)

By state law, for safety, each train had to be preceded by a man on horseback holding a warning flag or lantern and popularly known as a “Tenth Avenue Cowboy.”

As part of the original freight improvement project, which opened in 1934, the tracks from 60th to 34th streets were placed below street level, while the tracks south of 34th were elevated as the High Line (as seen here looking downtown near Gansevoort Street, now the site of the Gansevoort Woodland);

running to a new terminal, St. Johns Park, astride Houston Street. Note how the tracks ran through the warehouse building (now apartments) and the former Bell Telephone Labs (now Westbeth) in the distance. The freight trains that operated on the High Line directly served a number of factories, warehouses, and wholesale markets along the route, carrying goods from across America (some were reached by spur tracks using bridges like these still crossing Tenth Avenue near 16th Street).

But after 1945 rail freight declined as one by one these businesses closed or left the city. The last train ran in 1980, and the section south of Gansevoort Street was torn down.

The abandoned tracks were soon covered with a green carpet of weeds and shrubs (as seen in these photos by Joel Sternfeld. 2

Serious efforts to preserve the High Line began in 1999, when local residents Joshua David and Robert Hammond envisioned the abandoned, overgrown viaduct as an urban park—one they hoped would “retain the sense of wildness and mystery of the original High Line landscape…celebrat[ing] all that was great about the High Line’s past while making [it] accessible and giving it a future.” 3

Soon, this vision of a public space that would provide New Yorkers with scenes evoking the wildness of nature in the very midst of the most industrialized sections of Manhattan began to garner support from city officials as well as wealthy New Yorkers and hundreds of ordinary citizens. Organized as Friends of the High Line, they were able to obtain public and private funding of $86 million 4 and hire landscape architects James Corner Field Operations and architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro to design and carry out the transformation.

From Derelict Viaduct to Imaginative Urban Park

What does the High Line say about ourselves? People can feel at any age that life is passing them by, that there’s nothing new to expect, and as a person grows older he or she can feel one has outlived one’s usefulness. Yet the desire in people to find new meaning in the old High Line illustrates Eli Siegel’s sentences from his essay, “Declaration about Old Age”:

It is never too soon, never too late, never mistimed, to see the world honestly and to like it honestly. The message of Aesthetic Realism is this: The world is waiting for you to see it in a new way. 5

And this is what the High Line enables people to do: it shows us that new, vibrant life can come to an object thought of as no longer useful, as well as to a person who feels “I’ve seen it all.” This fact can encourage people to look at everything with fresh eyes.

Self and World: The High Line and Ourselves

In every person’s life the primary opposites are Self and World, which Mr. Siegel explains in sentences that are both intimate and wide:

We all of us start with a here, ever so snug and ever so immediate. And this here is surrounded strangely, endlessly by a there. We are always meeting this there, in other words,…what is not ourselves, and we have to do something about it. We have to be ourselves, and give to this great and diversified there,…what it deserves. 6

A large reason the High Line is so popular is because it meets the deep hope in every person to have oneself and one’s environment brought closer together. How does the High Line do this? It encourages a person to see himself or herself in relation to wild and cultivated plants,

old railroad tracks,

history,

other people,

streets, buildings old and new,

the broad Hudson River,

the wide sky, and clouds: in other words, to the expansive, multi-faceted natural and man-made world.

As we walk along the High Line,

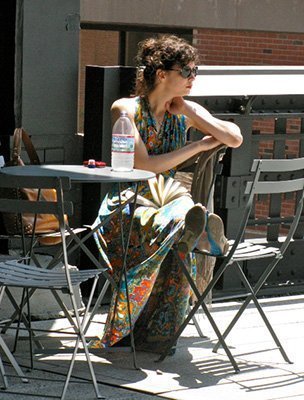

sit down, read, contemplate,

look around, talk with friends and strangers,

or watch a painter at work,

And looking eastward, one sees some of the former industrial aspects of the big city.

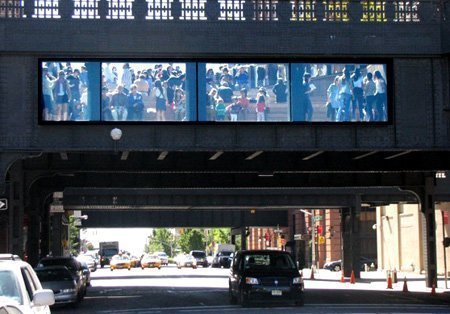

A particularly active, delightful joining of self and world is Tenth Avenue Square, sitting above that avenue between 16th and 17th streets.

It has rows of amphitheatre-style seats and large picture windows that invite visitors to sit, picnic, talk with each other, and look at cars and trucks rushing below.

The windows also allow people on the street to look up at the people seated above as if they were being viewed on a wide three-dimensional television screen.

Another aspect of self and world embodied by the High Line is the debate that has long been in people between the city and the country—between the busyness of the city,

and the restfulness of the country.

As Eli Siegel explained in a lecture titled “An Old Debate in Poetry: City and Country”: “Hubbub and quiet are some of the deepest things in a person’s mind. Reality is tumult and motion, it is also space and quiet.” 7

We have certainly had that debate. I, Faith Stern, as a New Yorker who loves the city, the crowds, its diversity, the busy motion of feet on hard pavement, also love restful beaches by the ocean. And I, John Stern, who grew up in a leafy suburb, like to drive in the country, enjoying mountains, woods, and old, tree-shaded streets. I used to insist I’d never live in New York City—even though my work as an urban and regional planner was concerned with its housing, office space, and transportation. Yet I now live in the city and love the intense vertical and horizontal excitement of Manhattan. We both learned that city and country are part of one world, and therefore both can be used to respect reality more, and learn about ourselves too.

The High Line combines city and country, “hubbub and quiet” in surprising ways. As visitors stroll, sit and relax,

observe a class of children,

and look around amid sky, distant vistas, tracks, and greenery, they see elements of both city and country and these are blended well.

The designers consciously thought about how to combine what they call “hard and soft” elements, and wrote:

It has always been our position to try to respect the innate character of the High Line itself: its singularity and linearity, its straight-forward pragmatism, its emergent properties with wild plant-life—meadows, thickets, vines, mosses, flowers, intermixed with ballast, steel tracks, railings, and concrete. 8

Imagination Can Be for or Against What Is Good

Looking at anything freshly requires imagination. However, as Aesthetic Realism explains, there are two kinds of imagination—one good and one bad: one on behalf of truth and the other on behalf of narrow ego. There is the imagination of Charles Dickens, Abraham Lincoln, and the people who created our national parks. Their purpose was to respect the world, have it more beautiful, more just. But there is also the imagination whose purpose is to have contempt for the world, and has taken the form of racism, wars of aggression, and the overweening personal greed that has made for the current economic disaster.

The creation of the High Line is an excellent example of good imagination. Through the careful thought and persistent efforts of founders Robert Hammond and Joshua David, the architects, public officials

and many others who envisioned the possibilities in this abandoned object, it has been transformed into something that is beautiful and useful. We have heard visitors say “Wow!,” “I never saw anything like this,” two young women said to us, “This is cool!," and we overheard a father explaining to his young son, "Here you're up in the air, in a garden in the sky, and you can still see the city.” Perfect strangers are impelled to talk to each other. The High Line can even be called romantic, because it puts together the opposites of the ordinary and the strange, transforming a former industrial facility into something almost magical—especially after sunset,

when it is subtly illuminated

and the windows in nearby buildings are lighted.

There Are Unity and Diversity

The High Line is one unified park, containing astonishing variety within its narrow width of from 30 to 60 feet and current length of just a mile.

In his historic Fifteen Questions, “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?,” Eli Siegel asks about oneness and manyness:

Is there in every work of art something which shows reality as one and also something which shows reality as many and diverse?—must every work of art have a simultaneous presence of oneness and manyness, unity and variety?9

Just as each of us is one person, with many thoughts, feelings, and relations with other people, so the High Line is a single object, yet shows within itself reality as “many and diverse.” In its short, nine-block length it has “neighborhoods,” including Gansevoort Woodland,

Washington Grassland,

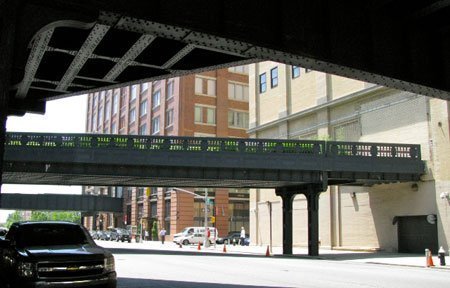

the Standard Hotel Underpass,

the tunnel under the mixed-use High Line Building,

Diller-von Furstenberg Sundeck,

Chelsea Market Passageway,

Tenth Avenue Square,

and Chelsea Grasslands.

As we have strolled along the High Line, the way each blends seamlessly into the next is somewhat like what we have felt walking in Central Park, as one section becomes the next without a break, creating the excitement of discovery with each step.

Joining all sections of the High Line are three elements: the tracks, the plantings, and the linear concrete planks that make up the flooring.

Some of the rails that were still in place from the 1930s were carefully re-laid in new alignments to give visitors a keen sense of the High Line’s former transportation uses. Meanwhile—and this is the feature that caught our attention as soon as we climbed the Gansevoort Street stairs—wild and cultivated nature is now an inseparable part of this hard steel structure. These plantings intentionally recall the carpet of weeds and shrubs that covered the abandoned High Line for years. The rails and switches remind us of the structure’s gritty industrial past, yet they are softened by the variegated, carefully planned vegetation—dozens of varieties of grasses, flowers, and saplings planted abundantly between and around the rails and walkways. This makes a surprising, dramatic, yet pleasing relation of the opposites of hardness and softness. It surprised and thrilled us to see purple, blue, or red blossoms partly concealing and blending with the tracks, yet it seems right—an effect that tracks or plants alone would not have.

Does this have a message for ourselves? Are we both hard and soft? Are we both iron and petals? And do we go back and forth—feeling too hard, driving at one moment, and too soft, agreeably yielding the next? How can we make sense of these opposites? The designers of the High Line were much affected seeing tender growing plant life coexisting with rusted metal making for something so satisfying. And as we observe this, it gives us hope because it stands for what we want to do—put hardness and softness together. And we come now to:

Separation and Junction: The High Line and Ourselves

One thing that struck us right away is how the High Line is both physically separate from everything around it, yet is joined to these things as well, because we can look out and see them. While we’re on top of a viaduct thirty feet in the air, we’re separate from streets, buildings, and the people below.

Yet we can look out and see these same streets, buildings near and far,

the river, and its far shore.

We can see people below walking or eating in restaurants—who may look at us in return.

So there is a pleasing and welcome drama here of separation and junction, near and far, the intimate and the wide.

The New Section Opens

A new section of the High Line, from 20th to 30th streets, opened in June 2011. This is the way it looked at 20th Street in 2010 while still under construction, which will help one understand how the park was built.

At this stage the tracks had already been re-laid on the surface of the original concrete foundation that rested on top of the heavy steel beams supporting the High Line. The linear concrete planks and their supports, including a comprehensive drainage system, were installed atop this foundation, becoming level with the tracks, and later shrubs and flowers would be planted amid the rails (as in this recent view).

At the opening of the new section, visitors were welcomed by a charming pair of sculptures flanking the walkway—just one example of the original art works that are displayed along the High Line from time to time. This one, “Still Life with Landscape,” by Sara Sze, featured large metal frameworks interspersed with rectangular boxes, some with food which attracted lively small birds who flew in and out of the installation, often pausing to perch and snack.

The High Line Is Narrow and Wide

This new ten-block segment has a somewhat different feeling from the first section because of the notable relation in it of the opposites of narrow and wide. Whereas the original half mile has striking open vistas, sheltered passageways, and a somewhat meandering course, the major portion of the new section is fairly straight and seems narrower as it runs close to buildings old, remodeled, and new—even futuristic—on both sides.

Therefore a visitor experiences a more enclosed, even canyon-like feeling,

which the designers took into account by introducing rich variety into this segment of the High Line. One example is the Thicket, a dense cluster of shrubs and short trees, beginning at 21st Street,

through which the narrow path threads its way and then makes a graceful left turn into a wide-open area—providing a sense of welcome space, and also mystery and suspense, as we ask: who will be turning that corner next?

And when we reach the 23rd Street Lawn,

we enter an expansive, lush greensward covering a tenth of an acre upon which park-goers read, picnic, socialize, and otherwise relax. The Lawn is bordered on one side by stadium-style teak benches, providing opportunity for resting and observing the scene before one.

Both the Lawn and part of the Thicket occupy a section of the High Line that was built wider to accommodate a third track (as shown near the top of the picture in this 1930s aerial view),

which served a warehouse loading platform where the teak benches now stand.

Beyond the Lawn and north of 24th Street, the walkway of the Lisa Maria and Philip A. Falcone Flyover begins to rise, reaching eight feet above the surface. You then walk level with the abundant leafy canopy of trees, while overlooking the rails and plants below.

As you stroll uptown, you can see the tree-shaded back yard of a mid-19th century house;

a narrow industrial alley;

a bench looking outward facing an open rectangular frame, intended to call to mind billboards which used to look out from the original High Line;

a distant glimpse of the Chrysler Buiding in Midtown;

and a distinctive pussycat.

Finally the High Line begins to descend—with expansive views once again of the city—

and curves past continuous wooden benches toward its present terminus at 30th Street.

There a section of the floor of the High Line is cut out to reveal the steel beams that make up the muscular structure needed to support heavy freight trains.

In a poem we love by Martha Baird, “Man and Nature in New York and Kansas,” there are these two lines:

“See what nature and man can do!/ See what nature and man can do!” 10

In the High Line, where man (man here of course includes woman) and nature have joined to create a unique park for the enjoyment of generations to come.

End Notes

1 New York Times, July 22, 2009. The number of visitors has far exceeded expectations. According to the High Line, visitors in 2010 totalled two million, increasing to 3.7 million during 2011, with nearly equal proportions of New Yorkers and out-of-towners—half of whom are from foreign lands. Visitors on weekends have numbered as many as 100,000.

2 Additional views can be seen in: Joel Sternfeld: Walking the High Line (Göttingen [Germany] Steidl, 2002)

3 Friends of the High Line, Designing the High Line (New York: Friends of the High Line, 2008, p. 7)

4 The Wall Street Journal, June 23, 2009. The next section, from 20th to 30th streets, cost $67 million (AM New York, May 29, 2011)

5 Eli Siegel, “Declaration about Old Age” (New York: Terrain Gallery, 1974)

6 Siegel, Self and World (New York: Definition Press, 1981, p. 91)

7 Siegel, “An Old Debate in Poetry: City and Country,” September 6, 1967

8 James Corner in Designing the High Line, p. 30

9 Siegel, “Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?” (New York: Terrain Gallery, 1955)

10 Martha Baird, Nice Deity (New York: Definition Press, 1955, p. 31)

Bibliography

Joshua David and Robert Hammond, High Line: The Inside Story of New York City's Park in the Sky (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011)

Copyright 2012

Color photography by Faith Stern, John Stern and Amy Dienes; archival photography from the Internet.